Shits and Giggles

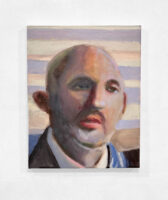

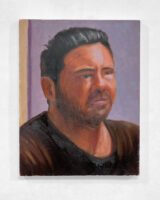

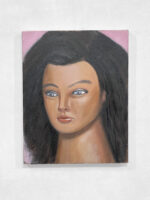

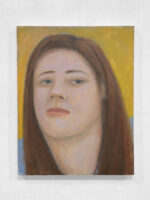

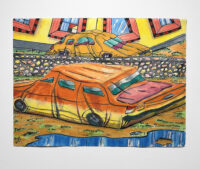

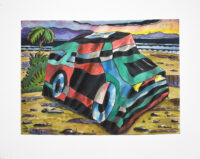

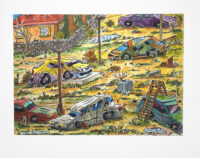

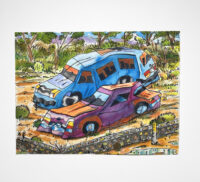

Cody Tumblin (wall works) and Keith Allyn Spencer (floor/pedestal works)

text by James Payne

Skylab Gallery

57 E. Gay Street, Columbus, OH

10/28 -11/11

(all photos courtesy of Skylab Gallery)

/ / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / /

Shits and Giggles in the Flow:

Keith Allyn Spencer & Cody Tumblin at Skylab Gallery

IS ART WRONG?

Of the lines I’ve written, “Is art wrong?” is by far the one my friends mock me with most often. It touches a nerve.

Is art wrong?

It doesn’t feel right.

That feeling – not right – is why essays on art, like this one, are often nothing but textual graves for dead, dying, and undead theories about our lives under capitalism. It’s easier to make a cogent argument about why the capitalist world leaves you nauseated, if, instead of making it about the world in all of its manifold complexity, you make it about the symbolic version of the world presented in art. But, for so long, the connection between the symbolic (art, art world) and the real (reality, world) was unclear; at best, it was that a change in the symbolic was like the wind – evident only through its observed effect on the real: blown trees, fallen leaves; new politics, shifting economies.

Now, however, the perennial goal of the avant-garde, to collapse art into life – the symbolic into the real – in order to unleash the radical potentialities of creativity in real-time, for all, has been achieved. It’s just that it’s only been achieved through the transmutation of both art and life into work. Still, if A (art) is B (work), and B (work) is C (life), then art has been collapsed into life after all, hasn’t it?

This new dynamic, besides making life easier for the Marxist art critic, has caused artists to engage in a para-politics centered on “the artist as worker,” (W.A.G.E, Arts & Labor) while also recuperating and fetishizing the concept of “art as play” as a refuge from, and evasion of, overprofessionalization.

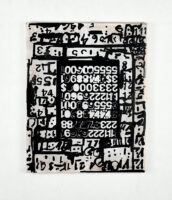

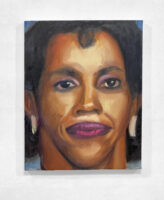

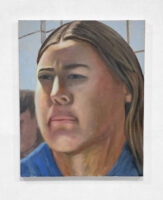

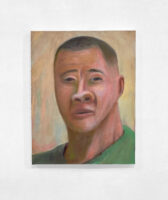

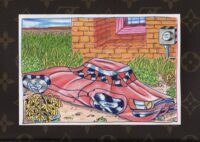

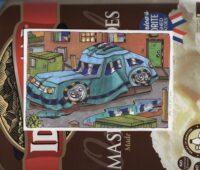

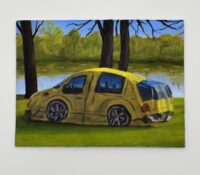

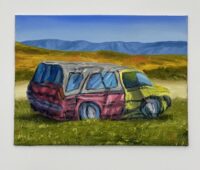

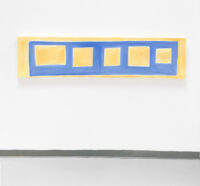

In Shits and Giggles, Keith Allyn Spencer, or KAS, (b. 1979; El Paso, TX) and Cody Tumblin (b. 1991; Franklin, TN) exhibit an example of the latter tendency, replete with a playful title, if ever there was one. Shits and Giggles is a painting show without paintings, with wall works that are on the ground, faux pedestals made of pizza boxes, fine art fabricated kitsch objects, unstretched canvases, unfinished works – anything to signal a non-compliance with the work of art and life’s rules, anything to signal play.

But if we conceptualize “play,” as Palo Alto does, as a free space where innovations are drawn from, to be capitalized upon later, then play is not an ecstatic experience of creative thought in either programming or art, but another site of a continued pain. The movement of “artist as worker” has likewise only been successful in the sense that there’s now a smattering of Social Practice TT positions, putting its re-enactments of bygone models of more humane economies into the service of the student-loan bubble.

The anxiety in some artists’ refusal to be serious, to conform to art’s new position as a profession, and to instead have Shits and Giggles, recalls Christopher Hsu’s essay “Spasm to Spasm” in Paper Monument #4 about the ever increasing need in arts circles to be on:

But now, whenever I hear a story or some inert bit of information, […] the question intrudes—So what is the funny side of this? Walking home from dinner or a party with the troubling thought, Possibly I was not funny enough tonight. And then there is email. Good or bad, there must be levity.

We’re all on now. Enjoying our lives. And our work. And our art. And doing all we can to be perceived on that level. KAS keeps “play” circulating by misusing titles, his mockubiography, fictional dates, and alternate spellings of his name to key the viewer into an ambient mischief, if the unorthodox hangings, materials, or exhibition sites failed to get it through. The antics of his poetics attempt to evade the staid, but the palpable anxiety to joke, already endemic in the artworld, creates a rhetorical nonspace where irony is de facto sincerity, and a joke just isn’t. This is why KAS’s employment of meme-derived language is so apt; titling a work Get You a Man Who Can Do Both is a tacit admission that the artwork on IRL display can only hint at its real conditions.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

ALMOST NOTHING

“All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.”

– Friedrich Engels & Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto

If the industrial revolution turned the real world and its relations into an air called modernity, and if post-modernity sold that air at an All That Is Solid Melts Into Air™ Oxygen bar, and if, in the recession, that bar closed – and if we’ve since been squatting in its basement – then we should all be honest and agree that we’re just vaping on a Marx-brand AIR E-Juice while we still can.

Or to put it another way: the role of the artist was world-simulator, then world-creator; it melted further into idea producer. Now, the artist produces the Idea of Production – vapes the idea of smoking.

The Idea of Production is doing something to put it on your CV so you can do something else later. It’s degrees that didn’t exist fifty, or five, years ago, for careers that stopped existing fifty, or five, years ago. It’s jobs that literally are not jobs. It’s finally showing at a gallery, but only after creating the gallery to show in. It’s What are you working on right now? and it’s always working right now, or it’s feeling embarrassed if you aren’t, or can’t, and it’s lying by saying that you are working, or want to. It’s the anxiety you feel when you aren’t feeling anxious enough, when you care too much about how you don’t care at all.

This Idea of Production is necessitated by Flow, which is the dominant paradigm of our lives as 2016 comes to a close. Flow is where we see the “real conditions of life” in which, Marx wrote, “all that is holy is profaned.” Though the Idea of Production is a response to Flow, it in turn energizes and normalizes its demands. In Flow, all facets of life become more and more commoditized, especially as there are less and less buyers on the market: the industrial space (57 E. Gay St. 5th FL) melts into the idea theater (Skylab Gallery), where events are attended by people whose careers have melted into 1099s, whose country is a collection of warring interest groups, whose family units are childless communes, whose relationships are mediated app hook-ups, whose houses are sub-sub-sublets, and whose Ubers are automated. All in Flow is flux, all is melt; even these examples are outdated, awaiting a new disintegration to come.

Flow triggers the need for artists to produce the Idea of Production just to tread water. Both Flow and the Idea of Production find their natural homes on Instagram, whose endless scroll of atomized lives formally reflects the melt of the real world economy. At the same time, the real world debases its own relations to fit the logic and display regimen of the scroll. This ever-morphing presentation and representation leaves one in vertigo, where all that is solid has melted into the social. Tourists become tourists of their own tourism just as an artist’s real art becomes who sees their art objects and how.

But no matter how productive, the artist can never fill Flow’s maw: post as many production shots, coterie shout-outs, inspo insights, residency humblebrags, on-brand political reposts, and studio visit pix on Flow’s abyss and it will only demand more the next day. Accordingly, the work of the artist is now spent maintaining their Flow. Flow has turned the artist’s objects into posts, posts into followers, followers into social capital, and social capital into real capital via gallery representation, academic jobs, and art sales. The art object, destabilized and commandeered by Flow, now exists to arbitrate, as an online avatar, connections, exhibitions, careers, friendships, partners, marriages, and future Flows for the artist. For instance, I first saw KAS’s work on Instagram, even though we were in the same Indiana University building each day; the same with Tumblin’s, though we had been in SAIC’s orbit at the same time.

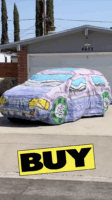

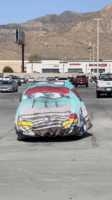

KAS and Tumblin are bright lights in this wave of denatured and accelerated production, whose Flow maintenance is integrated into and positively impacts the art objects they make. KAS’s work, for instance, is predicated on endless iteration in an attempt to meet and mirror the demands and opportunities of Flow within one piece. Works like 2016’s Everyday Is A Friday, a painting done on both sides of multiple pieces of jigsawed or laser-cut wood and placed on nails in the wall, recalling the jubilant Stellas of the 80s, are documented repeatedly, with multiple IG posts sharing possible permutations, and, during a studio visit, these permutations are further manipulated in real-time, and, depending on the install, may change again in the gallery, or when finally released into the wild by KAS at a Wal-Mart or other culturally-coded non-art site frequented by his family.

KAS’s GIFs extend this idea further in an attempt to embody Flow. KAS takes one of his manipulable painting/sculptures, which exist in the formal space of Jean Arp’s early-20th century bio-morphic reliefs, and loops the set of viable forms of each piece, which undermines the authority, or possibility, of an ultimate decision, and the idea of author in general, separating “author” from its “authoritarian” overtone. The GIFs instead point toward the endless, the open circuit, the experiential processes of creation – but also the variables involved in display and spectatorship, that ensure a work is never settled. Similarly, the GIFs are always present, always shifting, always now, while the art object in the past was understood as one of the only ways to simultaneously mark time and escape it – it’s always 1937 in Guernica. The GIFs, and Flow, neither mark nor escape time; it’s like looking for a clock in a casino.

Painting can no longer be George Tooker producing an egg tempera once a year that stands like a landmark Supreme Court decision through time, and not just because George Tooker is dead. Painting is now hundreds of permutational ideas, each a move in a Rubik’s Cube, a moment in a virtuoso act of problem-making and problem-solving, where each solution reveals a new problem, across an endless X-axis. Tumblin’s work inhabits this schema and the demands of a production-centered cultural economy because his work lives in on-going process. Motifs of spider webs and flames and decontextualized words sprint through series of Tumblin’s works where the one constant is a mercuriality – of style, of material, of representation, of display – that refuses to sit still and coagulate into a coherent – and therefore dead – world in the extended Flow of his work.

Within Flow, KAS and Tumblin’s art objects can be talked about like art, on one level, but, as posts, they will serve foremost as holders of sociality. Art and work and life delaminated from material conditions is not for us, or for Skylab, or an IRL gallery-going public, but for an audience who surveilles us through classism, racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, educationism, geographical proximity to capital, through who follows us back, through who comments; and yet we still post in the hopes that, after this, there is more. The actual art object in Flow appears to be the reason for everything, and yet is almost nothing.

When I ask Is Art Wrong? I think I am really asking if society is, and, while I’m not sure about art qua art, I know the correct answer to that question: Yup.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

But I also wrote this poem:

WHY DO I LOVE PAINTERS?

It’s just a thing poets do

like drawing attention

to the construction of the text.

I composed this poem

in a text

to a painter

as a sext.

As a poet, I can describe the world and my interior experience of it. One thing I can’t do is make something appear that is not there. Painters may no longer strive to make trompe l’oeil grapes so real-seeming that a viewer reaches out for them – instead they make sculptures that look like mass-produced fake poop that in turn looks like real shit – but even within the strictures of Flow and the Idea of Production, painters make things appear that were not there previously. And if one can see a change in the symbolic form of the world, it’s now the same as seeing it in the real one. Even if one sees it on Instagram.

The Shits and Giggles in the Flow is its only redemption.

James Payne

Berlin, October 2016